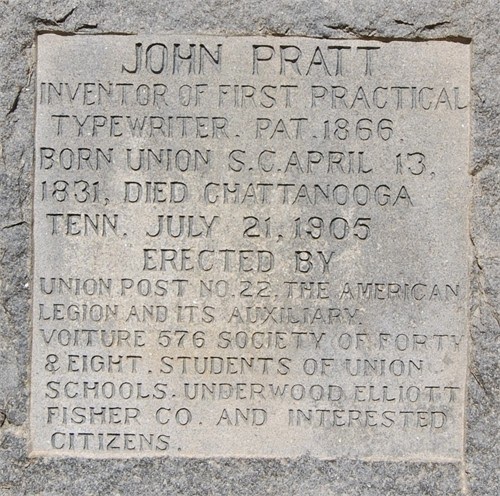

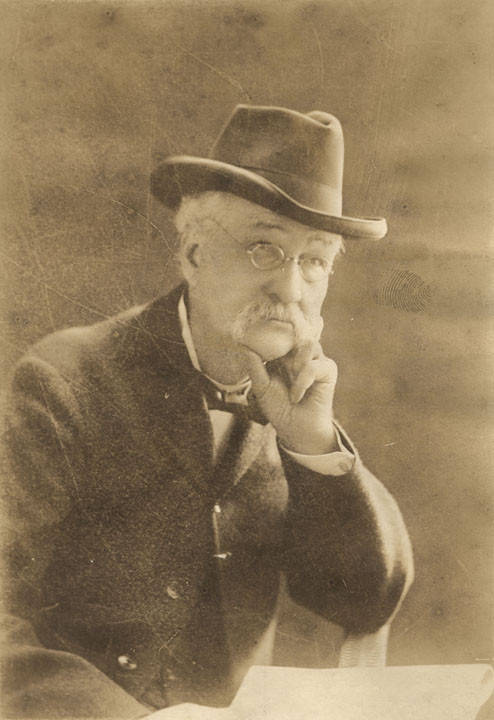

John Jonathan Pratt, the first American to invent a typewriter for sale to the public, was absolutely instrumental in the development, sale, and success of the Hammond typewriter. He may be the most overlooked inventor in typewriter history.

From his home in Centre, Alabama in 1860 he invented a type writing machine, capitalizing on his experience as editor of a newspaper. Had it not been for the Civil War he would have been able to patent and sell that machine in America. Instead he was forced to flee to Britain where he took refuge during the war, patented his machine and began selling to the public.

Born in South Carolina in 1831 his family moved soon thereafter to Centre, Alabama where he would spend most of his life. As part owner and editor of the Centre Democrat newspaper, he began working in secret on his invention and recruited the help of a printer named John Neely to fashion type for his machine. Together they would develop the first Pterotype, or “winged type” prototype in 1860.

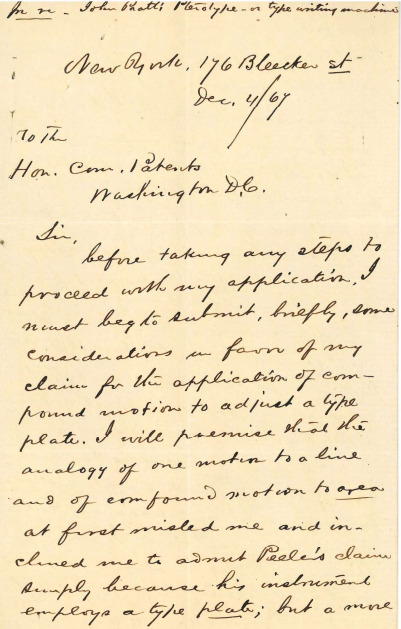

With the outbreak of the Civil War, and unable to get financial backing for his invention, Pratt found himself in a precarious position as a Confederate citizen. He also believed that he would not get a favorable reception with the United States Patent Office (USPTO), and he was deeply suspicious that his invention would be stolen.

As the Confederate States of America crumbled around him, Pratt moved to England in 1864 to pursue development of his invention. After gaining a British patent for his invention in 1866, Pratt teamed up with R. E. Burge, a London cabinet maker and upholster, to manufacture the first typewriter for sale to the public.

In that same year, Scientific American wrote an article about the Pterotype and the presentation he made to the London Society of the Arts. This article would inspire Christopher Latham Sholes to perfect his design of the typewriter, eventually bringing to market the Sholes and Glidden which we all know and love. Pratt’s ideas came before Sholes and Glidden, but his patent did not.

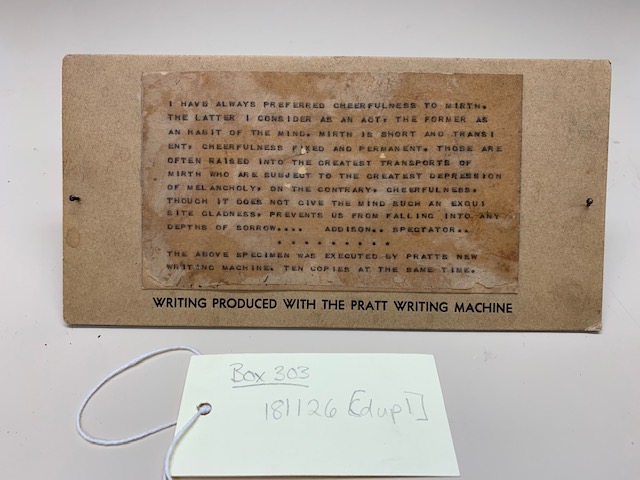

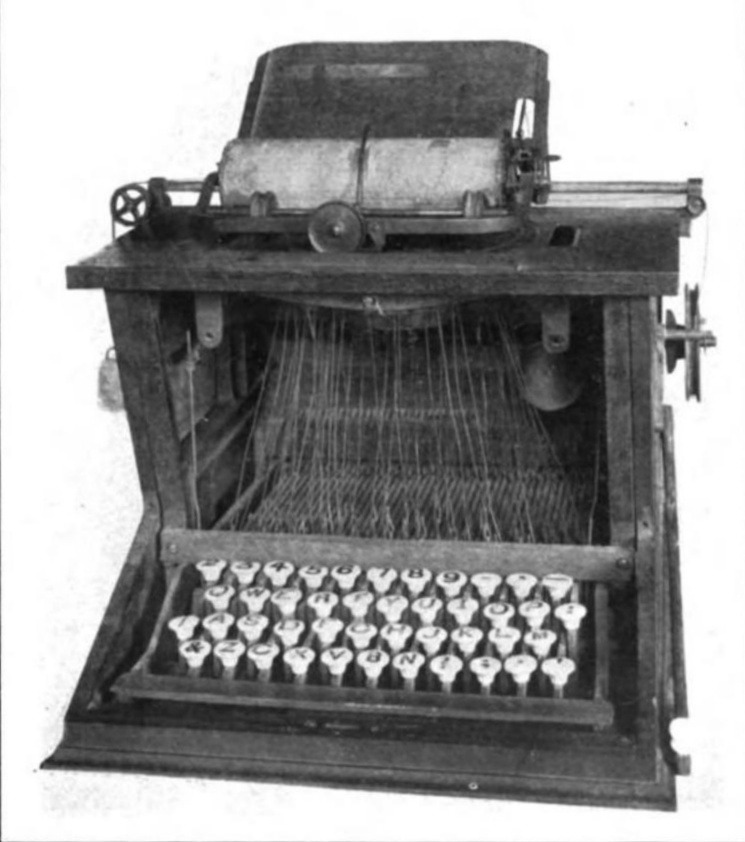

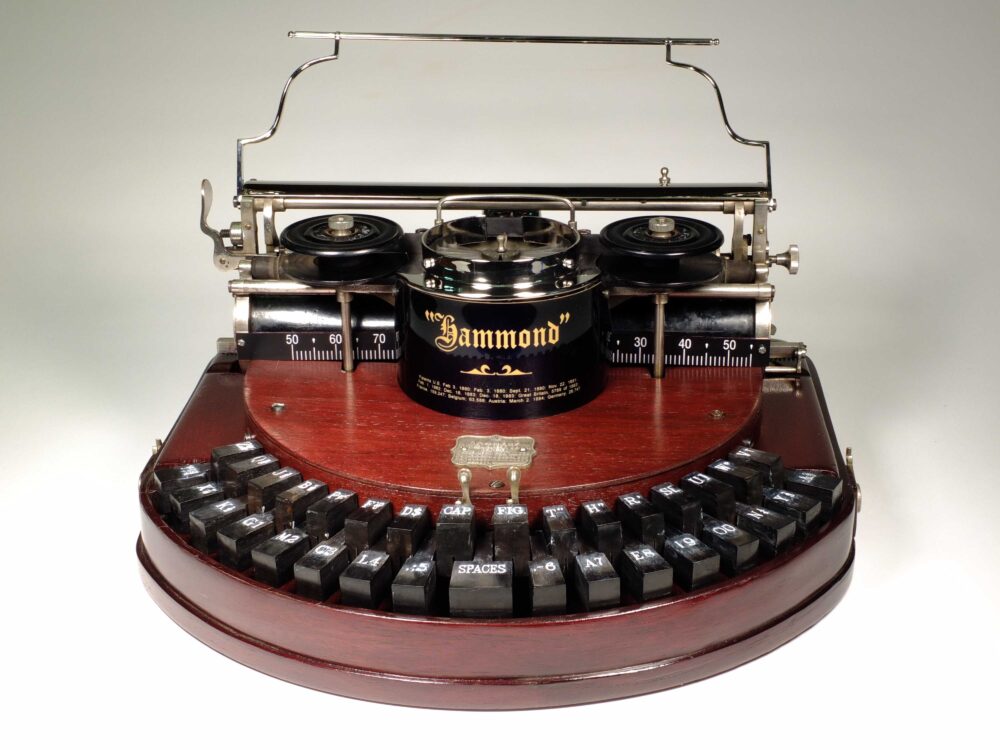

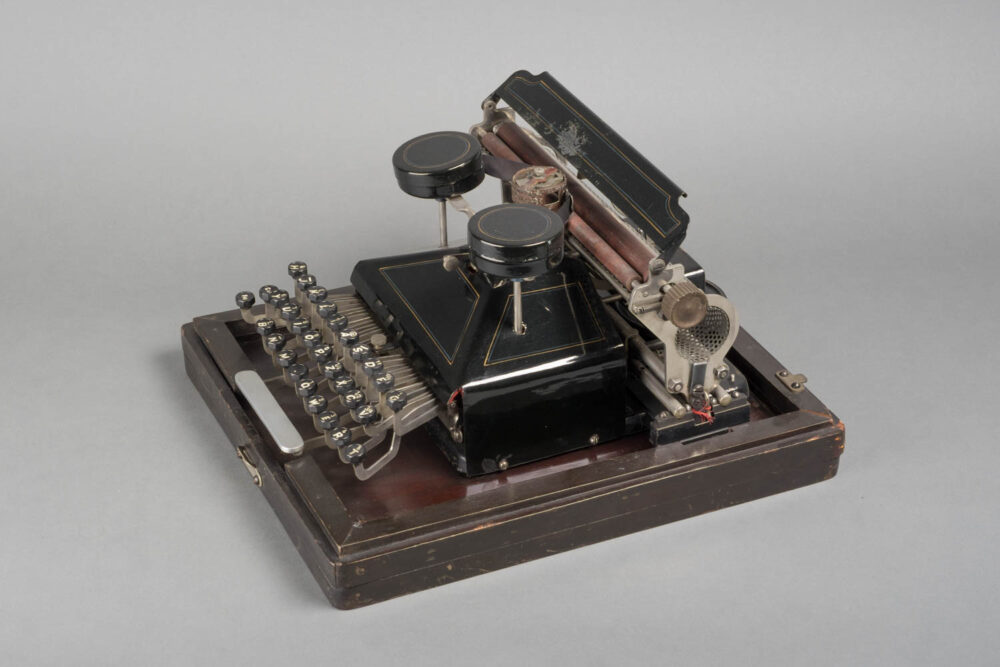

The machine had “36 characters…mounted in three rows of twelve each on a vertical type-wheel. Against this wheel a hammer strikes, so that an intervening paper with a carbon sheet receives the impression of the type.” The paper was affixed in a vertical frame which moved automatically after each letter is typed, with spacing accomplished by a partial depression of any one key. Two springs enabled the action of the paper carrier and “type wheel” although as shown in the accompanying photo, it is more of a type plate.

On May 30th, 1868 President Andrew Johnson issued an amnesty proclamation for most former Confederate citizens. This allowed Pratt to return home without fear of arrest. However, when he returned to America in the summer of 1868, he discovered that on June 23rd, 1868, Sholes had used the information gained from the Scientific American article to patent his own type-writing invention; U. S. patent number 79265.

Pratt did manage to file for a patent for refinements he had perfected resulting in United States patent number 81,000 issued on August 11, 1868.

Returning to Centre, Alabama he became editor of the Gadsden Times.

Then in 1877, financially broke and in some desperation, Pratt began looking to sell his 1868 patent, namely to Sholes and the Remington company. Neither would agree to a deal, Sholes had sold his half of the patent and moved back to Milwaukee, and Remington confident in its sleeker, or engineered design.

It also came to the attention of Lucian Crandall but Pratt declined to sell, with some saying it was due to Crandall’s distasteful attitude. Nevertheless, when Hammond wrote to Pratt in 1878, it took a little time for the two men to warm to one another.

Hammond arranged for Pratt to come to New York City for discussions. The two inventors hit it off immediately, bonding over their dislikes of the Remington typewriter, and people such as Crandall. The result of that meeting was an agreement: Hammond would purchase the 81,000 patent, and provide Pratt with a lifetime annuity.

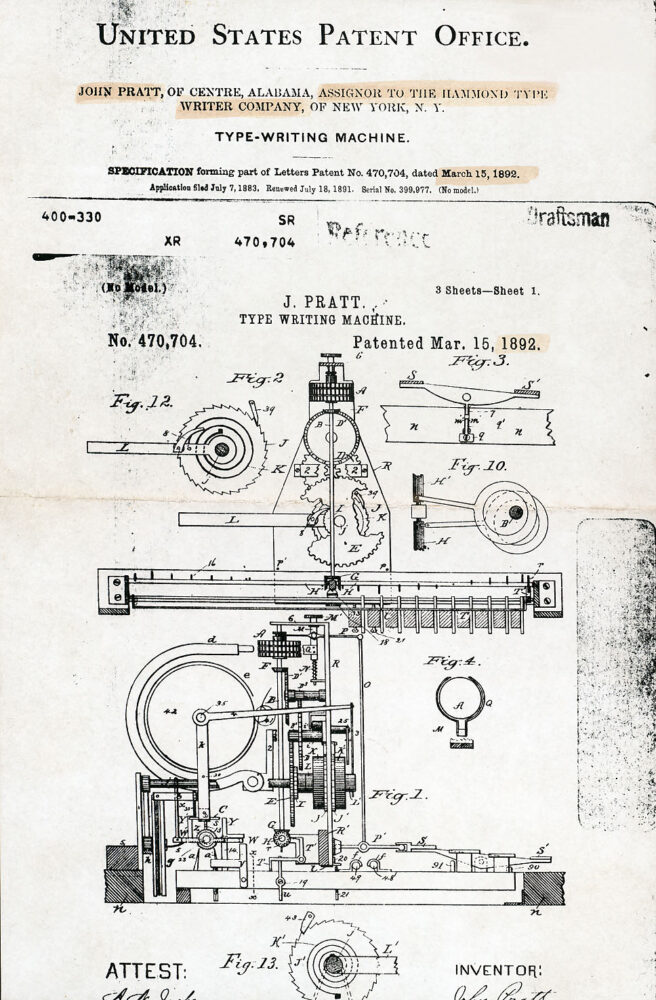

This agreement led to Hammond’s two patents in 1880, and the rest is undiscovered history. In 1879 Pratt filed another patent, assigning it to the Hammond typewriter company, for a machine that could type right-to-left, in particular for the printing of braille.

Mr. Pratt would continue to invent for Hammond, such as this “experimental” machine in 1892.

John Jonathon Pratt would die on June 24, 1905 in Chattanooga, Tennessee. For many years before his death, he lived in Brooklyn where he worked exclusively for the Hammond company.

His name is often forgotten and overlooked in the history of typewriters. If he had been born in a different place, perhaps a different time, there is no telling to what inventions he might have dreamed up.